[1] Wilson BS, Tucci DL, Merson MH, O'Donoghue GM : Global hearing health care: new findings and perspectives. Lancet 2017;390(10111):2503-2515

[2] Keithley EM : Pathology and mechanisms of cochlear aging. Journal of neuroscience research 2020;98(9):1674-1684

[3] Walling A, Dickson G : Hearing loss in older adults. American family physician 2012;85(12):1150-1156

[4] Gaylor JM, Raman G, Chung M, Lee J, Rao M, Lau J, Poe DS : Cochlear Implantation in Adults. JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery 2013;139(3):265

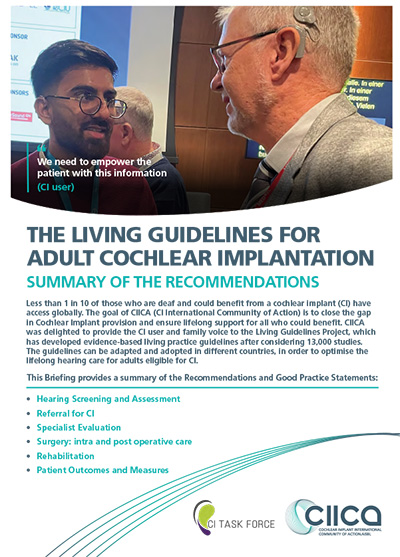

[5] Buchman CA, Gifford RH, Haynes DS, Lenarz T, O'Donoghue G, Adunka O, Biever A, Briggs RJ, Carlson ML, Dai PU, Driscoll CL, Francis HW, Gantz BJ, Gurgel RK, Hansen MR, Holcomb M, Karltorp E, Kirtane M, Larky J, Mylanus EAM, Roland JT, Saeed SR, Skarzynski H, Skarzynski PH, Syms M, Teagle H, Van de Heyning PH, Vincent C, Wu H, Yamasoba T, Zwolan T : Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery 2020;146(10):942-953

[6] Sorkin DL : Access to cochlear implantation. 2013;

[7] World Health Organization (WHO) : World report on hearing. (null) 2021;

[8] Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, Klein BE, Klein R., Mares-Perlman JA, Nondahl DM : Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148(9):879-86

[9] The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) : Diagnosis and management of hearing loss in elderly patients. Australian Journal for General Practitioners 2016;45 366-369

[10] Gates GA, Cobb JL, Linn RT, Rees T., Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB : Central auditory dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia in older people. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122(2):161-7

[11] Lin FR, Metter EJ, O'Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. : Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011;68(2):214-20

[12] Yueh B, Shapiro N, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG : Screening and Management of Adult Hearing Loss in Primary CareScientific Review. JAMA 2003;289(15):1976-1985

[13] Yawn R, Hunter JB, Sweeney AD, Bennett ML : Cochlear implantation: a biomechanical prosthesis for hearing loss. F1000 prime reports 2015;7 45-45

[14] Cochlear : Cochlear Limited Strategy Overview. 2020;

[15] Cochlear : How do cochlear implants work?. 2022;

[16] Yueh B, Shapiro N, MacLean CH, Shekelle PG : Screening and Management of Adult Hearing Loss in Primary CareScientific Review. JAMA 2003;289(15):1976-1985

[17] Gates GA, Cobb JL, Linn RT, Rees T., Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB : Central auditory dysfunction, cognitive dysfunction, and dementia in older people. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1996;122(2):161-7

[18] Lin FR, Metter EJ, O'Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. : Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011;68(2):214-20

[19] Sorkin DL, Buchman CA : Cochlear Implant Access in Six Developed Countries. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2016;37(2):e161-4

[20] Bierbaum M, McMahon CM, Hughes S, Boisvert I, Lau AYS, Braithwaite J, Rapport F : Barriers and Facilitators to Cochlear Implant Uptake in Australia and the United Kingdom. Ear and hearing 2020;41(2):374-385

[21] Sorkin DL : Cochlear implantation in the world's largest medical device market: utilization and awareness of cochlear implants in the United States. Cochlear implants international 2013;14 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S4-12

[22] World Health Organization (WHO) : Hearing Screening Considerations for Implementation. 2021;

[23] Strawbridge WJ, Wallhagen MI : Simple Tests Compare Well with a Hand-held Audiometer for Hearing Loss Screening in Primary Care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2017;65(10):2282-2284

[24] Deepthi R, Kasthuri A : Validation of the use of self-reported hearing loss and the Hearing Handicap Inventory for elderly among rural Indian elderly population. Archives of gerontology and geriatrics 2012;55(3):762-7

[25] Everett A, Wong A, Piper R, Cone B, Marrone N : Sensitivity and Specificity of Pure-Tone and Subjective Hearing Screenings Using Spanish-Language Questions. American journal of audiology 2020;29(1):35-49

[26] United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) : Hearing loss in older adults: screening. 2021;

[27] Carlson ML : Cochlear Implantation in Adults. The New England journal of medicine 2020;382(16):1531-1542

[28] Olusanya BO, Davis AC, Hoffman HJ : Hearing loss: rising prevalence and impact. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2019;97(10):646-646A

[29] Zwolan TA, Schvartz-Leyzac KC, Pleasant T : Development of a 60/60 Guideline for Referring Adults for a Traditional Cochlear Implant Candidacy Evaluation. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2020;41(7):895-900

[30] Ngombu SJ, Ray C, Vasil K, Moberly AC, Varadarajan VV : Development of a novel screening tool for predicting Cochlear implant candidacy. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology 2021;6(6):1406-1413

[31] Reddy P, Dornhoffer JR, Camposeo EL, Dubno JR, McRackan TR : Using Clinical Audiologic Measures to Determine Cochlear Implant Candidacy. Audiology & neuro-otology 2022;27(3):235-242

[32] Shim HJ, Won JH, Moon IJ, Anderson ES, Drennan WR, McIntosh NE, Weaver EM, Rubinstein JT : Can unaided non-linguistic measures predict cochlear implant candidacy?. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2014;35(8):1345-53

[33] Choi JE, Hong SH, Won JH, Park H-S, Cho YS, Chung W-H, Cho Y-S, Moon IJ : Evaluation of Cochlear Implant Candidates using a Non-linguistic Spectrotemporal Modulation Detection Test. Scientific reports 2016;6 35235

[34] Hunter JB, Tolisano AM : When to Refer a Hearing-impaired Patient for a Cochlear Implant Evaluation. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2021;42(5):e530-e535

[35] American Academy of Audiology : Clinical Practice Guidelines: Cochlear Implants. 2019;

[36] Christoph Loeffler AATBSKRLSA : Quality of Life Measurements after Cochlear Implantation. The Open Otorhinolaryngology Journal 2010;4 47-54

[37] Herr C, Bruschke S, Baumann U, Stöver T : Weißbuch Cochlea Implantat-Versorgung “-basierte Qualitätssicherung am Beispiel der „Audiologischen Basistherapie. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 2019;98(S 02):11117

[38] Katiri R, Hall DA, Killan CF, Smith S, Prayuenyong P, Kitterick PT : Systematic review of outcome domains and instruments used in designs of clinical trials for interventions that seek to restore bilateral and binaural hearing in adults with unilateral severe to profound sensorineural hearing loss ('single-sided deafness'). Current controlled trials in cardiovascular medicine 2021;22(1):220-220

[39] McRackan TR, Bauschard M., Hatch JL, Franko-Tobin E., Droghini HR, Velozo CA, Nguyen SA, Dubno JR : Meta-analysis of Cochlear Implantation Outcomes Evaluated With General Health-related Patient-reported Outcome Measures. Otol Neurotol 2018;39(1):29-36

[40] Ottaviani F., Iacona E., Sykopetrites V., Schindler A., Mozzanica F. : Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire into Italian. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology 2016;273(8):2001-2007

[41] Plath M., Marienfeld T., Sand M., van de Weyer PS, Praetorius M., Plinkert PK, Baumann I., Zaoui K. : Prospective study on health-related quality of life in patients before and after cochlear implantation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2022;279(1):115-125

[42] Santos NPD, Couto MIV, Martinho-Carvalho AC : Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire (NCIQ): translation, cultural adaptation, and application in adults with cochlear implants. CoDAS (São Paulo) 2017;29(6):e20170007-e20170007

[43] Hinderink JB, Krabbe PF, Van Den Broek P : Development and application of a health-related quality-of-life instrument for adults with cochlear implants: the Nijmegen cochlear implant questionnaire. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2000;123(6):756-65

[44] Technical Report Appendix D-H.

[45] Damen GWJA, Beynon AJ, Krabbe PFM, Mulder JJS, Mylanus EAM : Cochlear implantation and quality of life in postlingually deaf adults: long-term follow-up. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2007;136(4):597-604

[46] Kumar RS, Mawman D, Sankaran D, Melling C, O'Driscoll M, Freeman SM, Lloyd SKW : Cochlear implantation in early deafened, late implanted adults: Do they benefit?. Cochlear implants international 2016;17 Suppl 1 22-5

[47] Luxford WM, : Minimum speech test battery for postlingually deafened adult cochlear implant patients. Otolaryngology–head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 2001;124(2):125-6

[48] Assef RA, Almeida K., Miranda-Gonsalez EC : Sensitivity and specificity of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing Scale (SSQ5) for screening hearing in adults. CoDAS 2022;34(4) e20210106

[49] Balen SA, Vital BSB, Pereira RN, Lima TF, Barros D, Lopez EA, Diniz Junior J., Valentim RAM, Ferrari DV : Accuracy of affordable instruments for hearing screening in adults and the elderly. CoDAS 2021;33(5):e20200100

[50] Barczik J, Serpanos YC : Accuracy of Smartphone Self-Hearing Test Applications Across Frequencies and Earphone Styles in Adults. American journal of audiology 2018;27(4):570-580

[51] Bastianelli M., Mark AE, McAfee A., Schramm D., Lefrancois R., Bromwich M. : Adult validation of a self-administered tablet audiometer. Journal of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery 2019;48(1):59

[52] Becerril-Ramirez PB, Gonzalez-Sanchez DF, Gomez-Garcia A., Figueroa-Moreno R., Bravo-Escobar GA, Garcia de la Cruz MA : Hearing loss screening tests for adults. [Spanish]. Acta Otorrinolaringologica Espanola 2013;64(3) 184-190

[53] Boatman DF, Miglioretti DL, Eberwein C., Alidoost M., Reich SG : How accurate are bedside hearing tests?. Neurology 2007;68(16):1311-1314

[54] Bonetti L, Šimunjak B, Franić J : Validation of self-reported hearing loss among adult Croatians: the performance of the Hearing Self-Assessment Questionnaire against audiometric evaluation. International journal of audiology 2018;57(1):1-9

[55] Bourn S., Goldstein MR, Knickerbocker A., Jacob A. : Decentralized Cochlear Implant Programming Network Improves Access, Maintains Quality, and Engenders High Patient Satisfaction. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2021;42(8) 1142-1148

[56] Brennan-Jones CG, Eikelboom RH, Swanepoel W. : Diagnosis of hearing loss using automated audiometry in an asynchronous telehealth model: A pilot accuracy study. Journal of telemedicine and telecare 2017;23(2) 256-262

[57] Brennan-Jones CG, Taljaard DS, Brennan-Jones SE, Bennett RJ, Swanepoel de W., Eikelboom RH : Self-reported hearing loss and manual audiometry: A rural versus urban comparison. The Australian journal of rural health 2016;24(2) 130-135

[58] Bright T., Mulwafu W., Phiri M., Ensink RJH, Smith A., Yip J., Mactaggart I., Polack S. : Diagnostic accuracy of non-specialist versus specialist health workers in diagnosing hearing loss and ear disease in Malawi. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2019;24(7) 817-828

[59] Canete OM, Marfull D., Torrente MC, Purdy SC : The Spanish 12-item version of the Speech, Spatial and Qualities of Hearing scale (Sp-SSQ12): adaptation, reliability, and discriminant validity for people with and without hearing loss. Disability and rehabilitation 2020; 1-8

[60] Cardoso CL, Bos AJ, Goncalves AK, Olchik MR, Flores LS, Seimetz BM, Bauer MA, Coradini PP, Teixeira AR : Sensitivity and specificity of portable hearing screening in middle-aged and older adults. International @rchives of Otorhinolaryngology 2014;18(1):21-6

[61] Chayaopas N, Kasemsiri P, Thanawirattananit P, Piromchai P, Yimtae K : The effective screening tools for detecting hearing loss in elderly population: HHIE-ST Versus TSQ. BMC geriatrics 2021;21(1):1-9

[62] Colsman A., Supp GG, Neumann J., Schneider TR : Evaluation of Accuracy and Reliability of a Mobile Screening Audiometer in Normal Hearing Adults. Frontiers in Psychology 2020;11 744

[63] Dambha T., Swanepoel W., Mahomed-Asmail F., De Sousa KC, Graham MA, Smits C. : Improving the Efficiency of the Digits-in-Noise Hearing Screening Test: A Comparison Between Four Different Test Procedures. Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR 2022;65(1) 378-391

[64] Diao M., Sun J., Jiang T., Tian F., Jia Z., Liu Y., Chen D. : Comparison between self-reported hearing and measured hearing thresholds of the elderly in China. Ear and hearing 2014;35(5) e228-e232

[65] Dillon H., Beach EF, Seymour J., Carter L., Golding M. : Development of Telscreen: a telephone-based speech-in-noise hearing screening test with a novel masking noise and scoring procedure. International journal of audiology 2016;55(8) 463-471

[66] Folmer RL, Vachhani J., McMillan GP, Watson C., Kidd GR, Feeney MP : Validation of a computer-administered version of the digits-in-noise test for hearing screening in the United States. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2017;28(2) 161-169

[67] Fredriksson S., Hammar O., Magnusson L., Kahari K., Persson Waye K. : Validating self-reporting of hearing-related symptoms against pure-tone audiometry, otoacoustic emission, and speech audiometry. International journal of audiology 2016;55(8) 454-462

[68] Hong O., Ronis DL, Antonakos CL : Validity of self-rated hearing compared with audiometric measurement among construction workers. Nursing Research 2011;60(5) 326-332

[69] Ito K., Naito R., Murofushi T., Iguchi R. : Questionnaire and interview in screening for hearing impairment in adults. Acta Oto-Laryngologica (Supplement) 2007;127 24-28

[70] Jansen S., Luts H., Dejonckere P., van Wieringen A., Wouters J. : Efficient hearing screening in noise-exposed listeners using the digit triplet test. Ear and hearing 2013;34(6) 773-778

[71] Jupiter T. : Screening for hearing loss in the elderly using distortion product otoacoustic emissions, pure tones, and a self-assessment tool. American journal of audiology 2009;18(2) 99-107

[72] Kam ACS, Fu CHT : Screening for hearing loss in the Hong Kong Cantonese-speaking elderly using tablet-based pure-tone and word-in-noise test. International journal of audiology 2020;59(4):301-309

[73] Kelly EA, Stadler ME, Nelson S, Runge CL, Friedland DR : Tablet-based Screening for Hearing Loss: Feasibility of Testing in Nonspecialty Locations. Otology & Neurotology 2018;39(4):410-416

[74] Koleilat A, Argue DP, Schimmenti LA, Ekker SC, Poling GL : The GoAudio Quantitative Mobile Audiology Test Enhances Access to Clinical Hearing Assessments. American journal of audiology 2020;29(4):887-897

[75] Koole A, Nagtegaal AP, Homans NC, Hofman A, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Goedegebure A : Using the Digits-In-Noise Test to Estimate Age-Related Hearing Loss. Ear & Hearing (01960202) 2016;37(5):508-513

[76] Li LYJ, Wang SY, Wu CJ, Tsai CY, Wu TF, Lin YS : Screening for Hearing Impairment in Older Adults by Smartphone-Based Audiometry, Self-Perception, HHIE Screening Questionnaire, and Free-Field Voice Test: Comparative Evaluation of the Screening Accuracy With Standard Pure-Tone Audiometry. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2020;8(10) e17213

[77] Li LYJ, Wang SY, Yang JM, Chen CJ, Tsai CY, Wu LYY, Wu TF, Wu CJ : Validation of a personalized hearing screening mobile health application for persons with moderate hearing impairment. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2021;11(10) (no pagination)

[78] Livshitz L., Ghanayim R., Kraus C., Farah R., Even-Tov E., Avraham Y., Sharabi-Nov A., Gilbey P. : Application-Based Hearing Screening in the Elderly Population. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 2017;126(1) 36-41

[79] Lycke M., Boterberg T., Martens E., Ketelaars L., Pottel H., Lambrecht A., Van Eygen K., De Coster L., Dhooge I., Wildiers H., Debruyne PR : Implementation of uHearTM – an iOS-based application to screen for hearing loss – in older patients with cancer undergoing a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Journal of Geriatric Oncology 2016;7(2) 126-133

[80] Lycke M., Debruyne PR, Lefebvre T., Martens E., Ketelaars L., Pottel H., Van Eygen K., Derijcke S., Werbrouck P., Vergauwe P., Stellamans K., Clarysse P., Dhooge I., Schofield P., Boterberg T. : The use of uHearTM to screen for hearing loss in older patients with cancer as part of a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Acta Clinica Belgica: International Journal of Clinical and Laboratory Medicine 2018;73(2) 132-138

[81] McShefferty D., Whitmer WM, Swan IRC, Akeroyd MA : The effect of experience on the sensitivity and specificity of the whispered voice test: A diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open 2013;3(4) (no pagination)

[82] Mosites E., Neitzel R., Galusha D., Trufan S., Dixon-Ernst C., Rabinowitz P. : A comparison of an audiometric screening survey with an in-depth research questionnaire for hearing loss and hearing loss risk factors. International journal of audiology 2016;55(12) 782-786

[83] Paglialonga A, Grandori F, Tognola G : Using the Speech Understanding in Noise (SUN) Test for Adult Hearing Screening. American journal of audiology 2013;22(1):171-174

[84] Paglialonga A., Tognola G., Grandori F. : A user-operated test of suprathreshold acuity in noise for adult hearing screening: The SUN (SPEECH UNDERSTANDING IN NOISE) test. Computers in Biology and Medicine 2014;52 66-72

[85] Parving A., Sorup Sorensen M., Christensen B., Davis A. : Evaluation of a hearing screener. Audiological Medicine 2008;6(2) 115-119

[86] Qi BE, Zhang TB, Fu XX, Li GP : [Establishment of the characterization of an adult digits-in-noise test based on internet]. Lin Chuang Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi = Journal Of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology, Head, & Neck Surgery 2018;32(3):202-205

[87] Ramkissoon I., Cole M. : Self-reported hearing difficulty versus audiometric screening in younger and older smokers and nonsmokers. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 2011;3(4):183-90

[88] Rodrigues LC, Ferrite S., Corona AP : Validity of hearTest Smartphone-Based Audiometry for Hearing Screening in Workers Exposed to Noise. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2021;32(2) 116-121

[89] Saliba J, Al-Reefi M, Carriere JS, Verma N, Provencal C, Rappaport JM : Accuracy of Mobile-Based Audiometry in the Evaluation of Hearing Loss in Quiet and Noisy Environments. Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery 2017;156(4):706-711

[90] Salonen J., Johansson R., Karjalainen S., Vahlberg T., Isoaho R. : Relationship between self-reported hearing and measured hearing impairment in an elderly population in Finland. International journal of audiology 2011;50(5) 297-302

[91] Sandstrom J., Swanepoel D., Laurent C., Umefjord G., Lundberg T. : Accuracy and Reliability of Smartphone Self-Test Audiometry in Community Clinics in Low Income Settings: A Comparative Study. Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology 2020;129(6):578-584

[92] Seluakumaran K., Shaharudin MN : Calibration and initial validation of a low-cost computer-based screening audiometer coupled to consumer insert phone-earmuff combination for boothless audiometry. International journal of audiology 2021; 1-9

[93] Sheikh Rashid M, Leensen MCJ, de Laat JAPM, Dreschler WA : Laboratory evaluation of an optimised internet-based speech-in-noise test for occupational high-frequency hearing loss screening: Occupational Earcheck. International journal of audiology 2017;56(11):844-853

[94] Skjonsberg A., Heggen C., Jamil M., Muhr P., Rosenhall U. : Sensitivity and Specificity of Automated Audiometry in Subjects with Normal Hearing or Hearing Impairment. Noise & health 2019;21(98) 1-6

[95] Szudek J., Ostevik A., Dziegielewski P., Robinson-Anagor J., Gomaa N., Hodgetts B., Ho A. : Can uHear me now? Validation of an iPod-based hearing loss screening test. Journal of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery 2012;41(SUPPL. 1) S78-S84

[96] Thodi C., Parazzini M., Kramer SE, Davis A., Stenfelt S., Janssen T., Smith P., Stephens D., Pronk M., Anteunis LI, Schirkonyer V., Grandori F. : Adult Hearing Screening: Follow-Up and Outcomes. American journal of audiology 2013;22(1):183-185

[97] Tomioka K., Ikeda H., Hanaie K., Morikawa M., Iwamoto J., Okamoto N., Saeki K., Kurumatani N. : The Hearing Handicap Inventory for Elderly-Screening (HHIE-S) versus a single question: reliability, validity, and relations with quality of life measures in the elderly community, Japan. Quality of life research : an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation 2013;22(5) 1151-1159

[98] Torres-Russotto D., Landau WM, Harding GW, Bohne BA, Sun K., Sinatra PM : Calibrated finger rub auditory screening test (CALFRAST). Neurology 2009;72(18) 1595-1600

[99] Vaez N., Desgualdo-Pereira L., Paglialonga A. : Development of a Test of Suprathreshold Acuity in Noise in Brazilian Portuguese: A New Method for Hearing Screening and Surveillance. BioMed Research International 2014;2014 (no pagination)

[100] Vaidyanath R, Yathiraj A : Relation Between the Screening Checklist for Auditory Processing in Adults and Diagnostic Auditory Processing Test Performance. American journal of audiology 2021;30 688-702

[101] Vercammen C., Goossens T., Wouters J., van Wieringen A. : Digit Triplet Test Hearing Screening With Broadband and Low-Pass Filtered Noise in a Middle-Aged Population. Ear and hearing 2018;39(4) 825-828

[102] Wang Y., Mo L., Li Y., Zheng Z., Qi Y. : Analysing use of the Chinese HHIE-S for hearing screening of elderly in a northeastern industrial area of China. International journal of audiology 2017;56(4):242-247

[103] Watson CS, Kidd GR, Miller JD, Smits C, Humes LE : Telephone Screening Tests for Functionally Impaired Hearing: Current Use in Seven Countries and Development of a US Version. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2012;23(10):757-767

[104] Williams-Sanchez V., McArdle RA, Wilson RH, Kidd GR, Watson CS, Bourne AL : Validation of a screening test of auditory function using the telephone. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2014;25(10) 937-951

[105] You S., Han W., Kim S., Maeng S., Seo YJ : Reliability and validity of self-screening tool for hearing loss in older adults. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2020;15 75-82

[106] Zanet M., Polo EM, Lenatti M., Van Waterschoot T., Mongelli M., Barbieri R., Paglialonga A. : Evaluation of a Novel Speech-in-Noise Test for Hearing Screening: Classification Performance and Transducers' Characteristics. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2021;25(12) 4300-4307

[107] Zhang M, Bi Z, Fu X, Wang J, Ruan Q, Zhao C, Duan J, Zeng X, Zhou D, Chen J, Bao Z : A parsimonious approach for screening moderate-to-profound hearing loss in a community-dwelling geriatric population based on a decision tree analysis. BMC geriatrics 2019;19(1):N.PAG-N.PAG

[108] Zimatore G., Cavagnaro M., Skarzynski PH, Fetoni AR, Hatzopoulos S. : Detection of age-related hearing losses (Arhl) via transient-evoked otoacoustic emissions. Clinical Interventions in Aging 2020;15 927-935

[109] Frank A., Goldlist S., Mark Fraser AE, Bromwich M. : Validation of SHOEBOX QuickTest Hearing Loss Screening Tool in Individuals With Cognitive Impairment. Front Digit Health 2021;3 724997

[110] Marinelli JP, Lohse CM, Fussell WL, Petersen RC, Reed NS, Machulda MM, Vassilaki M, Carlson ML : Association between hearing loss and development of dementia using formal behavioural audiometric testing within the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging (MCSA): a prospective population-based study. The Lancet. Healthy longevity 2022;3(12):e817-e824

[111] NIH National Institute on Aging (NIA) : Hearing Loss: A Common Problem for Older Adults. 2018;

[112] Aylward A, Gordon SA, Murphy-Meyers M, Allen CM, Patel NS, Gurgel RK : Caregiver Quality of Life After Cochlear Implantation in Older Adults. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2022;43(2):e191-e197

[113] Gurgel RK, Duff K, Foster NL, Urano KA, deTorres A : Evaluating the Impact of Cochlear Implantation on Cognitive Function in Older Adults. The Laryngoscope 2022;132 Suppl 7(Suppl 7):S1-S15

[114] Mosnier I, Vanier A, Bonnard D, Lina-Granade G, Truy E, Bordure P, Godey B, Marx M, Lescanne E, Venail F, Poncet C, Sterkers O, Belmin J : Long-Term Cognitive Prognosis of Profoundly Deaf Older Adults After Hearing Rehabilitation Using Cochlear Implants. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2018;66(8):1553-1561

[115] Yeo BSY, Song HJJMD, Toh EMS, Ng LS, Ho CSH, Ho R, Merchant RA, Tan BKJ, Loh WS : Association of Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants With Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA neurology 2022;

[116] Lee DS, Herzog JA, Walia A, Firszt JB, Zhan KY, Durakovic N, Wick CC, Buchman CA, Shew MA : External Validation of Cochlear Implant Screening Tools Demonstrates Modest Generalizability. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2022;43(9):e1000-e1007

[117] Aural Rehabilitation Clinical Practice Guideline Development Panel, Basura G, Cienkowski K, Hamlin L, Ray C, Rutherford C, Stamper G, Schooling T, Ambrose J : American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Clinical Practice Guideline on Aural Rehabilitation for Adults With Hearing Loss. American journal of audiology 2022; 1-51

[118] American Academy of Audiology : Clinical Practice Guidelines: Cochlear Implants. 2019;

[119] Britich Cochlear Implant Group : Quality Standards Cochlear Implant Services for Children and Adults. 2018;

[120] British Society of Hearing Aid Audiologists : Referral Guidelines for HCPC registered Hearing Aid Dispensers. 2017;

[121] Buchman CA, Gifford RH, Haynes DS, Lenarz T., O'Donoghue G., Adunka O., Biever A., Briggs RJ, Carlson ML, Dai P., Driscoll CL, Francis HW, Gantz BJ, Gurgel RK, Hansen MR, Holcomb M., Karltorp E., Kirtane M., Larky J., Mylanus EAM, Roland JTJ, Saeed SR, Skarzynski H., Skarzynski PH, Syms M., Teagle H., Van de Heyning PH, Vincent C., Wu H., Yamasoba T., Zwolan T. : Unilateral Cochlear Implants for Severe, Profound, or Moderate Sloping to Profound Bilateral Sensorineural Hearing Loss: A Systematic Review and Consensus Statements. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;146(10):942-953

[122] German Society of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology HANS : Cochlear implant (CI) fitting. 2018;

[123] Hermann R., Lescanne E., Loundon N., Barone P., Belmin J., Blanchet C., Borel S., Charpiot A., Coez A., Deguine O., Farinetti A., Godey B., Lazard D., Marx M., Mosnier I., Nguyen Y., Teissier N., Virole MB, Roman S., Truy E. : French Society of ENT (SFORL) guidelines. Indications for cochlear implantation in adults. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 2019;136(3):193-197

[124] Herr C, Bruschke S, Baumann U, Stöver T : Weißbuch Cochlea Implantat-Versorgung “-basierte Qualitätssicherung am Beispiel der „Audiologischen Basistherapie. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie 2019;98(S 02):11117

[125] Holder JT, Holcomb MA, Snapp H, Labadie RF, Vroegop J, Rocca C, Elgandy MS, Dunn C, Gifford RH : Guidelines for Best Practice in the Audiological Management of Adults Using Bimodal Hearing Configurations. Otology & Neurotology Open 2022;2(2):

[126] Jeffery H, Jennings S, Turton L : Guidance for Audiologists: Onward Referral of Adults with Hearing Difficulty Directly Referred to Audiology Services. 2016;

[127] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence : Hearing loss in adults: assessment and management. 2018;

[128] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence : Cochlear implants for children and adults with severe to profound deafness. 2019;

[129] Turton L., Souza P., Thibodeau L., Hickson L., Gifford R., Bird J., Stropahl M., Gailey L., Fulton B., Scarinci N., Ekberg K., Timmer B. : Guidelines for Best Practice in the Audiological Management of Adults with Severe and Profound Hearing Loss. Semin Hear 2020;41(3):141-246

[130] United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) : Hearing loss in older adults: screening. 2021;

[131] Western Australia Department of Health : Clinical Guidelines for Adult Cochlear Implantation. 2011;

[132] Vogel JP, Dowswell T, Lewin S, Bonet M, Hampson L, Kellie F, Portela A, Bucagu M, Norris SL, Neilson J, Gülmezoglu AM, Oladapo OT : Developing and applying a 'living guidelines' approach to WHO recommendations on maternal and perinatal health. BMJ global health 2019;4(4):e001683

[133] Bennett RJ, Fletcher S, Conway N, Barr C : The role of the general practitioner in managing age-related hearing loss: perspectives of general practitioners, patients and practice staff. BMC family practice 2020;21(1):87

[134] McRackan TR, Hand BN, Velozo CA, Dubno JR, : Validity and reliability of the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL)-35 Profile and CIQOL-10 Global instruments in comparison to legacy instruments. Ear and hearing 2021;42(4):896-908

[135] Laplante-Lévesque A, Dubno JR, Mosnier I, Ferrary E, McRackan TR : Best Practices in the Development, Translation, and Cultural Adaptation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures for Adults With Hearing Impairment: Lessons From the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life Instruments. Frontiers in neuroscience 2021;15 718416

[136] McRackan TR, Velozo CA, Holcomb MA, Camposeo EL, Hatch JL, Meyer TA, Lambert PR, Melvin CL, Dubno JR : Use of Adult Patient Focus Groups to Develop the Initial Item Bank for a Cochlear Implant Quality-of-Life Instrument. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery 2017;143(10):975-982

[137] McRackan TR, Hand BN, , Velozo CA, Dubno JR : Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL): Development of a Profile Instrument (CIQOL-35 Profile) and a Global Measure (CIQOL-10 Global). Journal of speech, language, and hearing research : JSLHR 2019;62(9):3554-3563

[138] McRackan TR, Hand BN, Velozo CA, Dubno JR, : Development of the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life Item Bank. Ear and hearing 2019;40(4):1016-1024

[139] McRackan TR, Hand BN, Chidarala S, Dubno JR : Understanding Patient Expectations Before Implantation Using the Cochlear Implant Quality of Life-Expectations Instrument. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery 2022;148(9):870-878

[140] McRackan TR, Hand BN, Chidarala S, Velozo CA, Dubno JR, : Normative Cochlear Implant Quality of Life (CIQOL)-35 Profile and CIQOL-10 Global Scores for Experienced Cochlear Implant Users from a Multi-Institutional Study. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology 2022;43(7):797-802

[141] Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, Ames D, Ballard C, Banerjee S, Brayne C, Burns A, Cohen-Mansfield J, Cooper C, Costafreda SG, Dias A, Fox N, Gitlin LN, Howard R, Kales HC, Kivimäki M, Larson EB, Ogunniyi A, Orgeta V, Ritchie K, Rockwood K, Sampson EL, Samus Q, Schneider LS, Selbæk G, Teri L, Mukadam N : Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet (London, England) 2020;396(10248):413-446

[142] Völter C, Götze L, Ballasch I, Harbert L, Dazert S, Thomas JP : Third-party disability in cochlear implant users. 2021;

[143] Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, Koch LL, Celani KE, Lopez IP, Williams VA : Hearing and balance screening and referrals for Medicare patients: a national survey of primary care physicians. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2008;19(2):171-90

[144] Parving A, Christensen B, Sørensen MS : Primary physicians and the elderly hearing-impaired. Actions and attitudes. Scandinavian audiology 1996;25(4):253-8

[145] Schneider JM, Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Britt HC, Harrison CM, Usherwood T, Leeder SR, Mitchell P : Role of general practitioners in managing age-related hearing loss. The Medical journal of Australia 2010;192(1):20-3

[146] Runge CL, Henion K, Tarima S, Beiter A, Zwolan TA : Clinical Outcomes of the Cochlear™ Nucleus(®) 5 Cochlear Implant System and SmartSound™ 2 Signal Processing. Journal of the American Academy of Audiology 2016;27(6):425-440

[147] Gaylor JM, Raman G, Chung M, Lee J, Rao M, Lau J, Poe DS : Cochlear implantation in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery 2013;139(3):265-72

[148] Sanchez-Cuadrado I, Gavilan J, Perez-Mora R, Muñoz E, Lassaletta L : Reliability and validity of the Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire in Spanish. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology – Head and Neck Surgery 2015;272(7):1621-5

[149] Plath M, Sand M, van de Weyer PS, Baierl K, Praetorius M, Plinkert PK, Baumann I, Zaoui K : [Validity and reliability of the Nijmegen Cochlear Implant Questionnaire in German]. HNO 2022;70(6):422-435

[150] British Cochlear Implant Group : The rehabilitation process. n.d.;

[151] Cochlear Implant International Community of Action (CIICA) : CIICA Conversation: Adults with CI talking about the Living Guidelines Project 3: 24 October 2022. 2022;

[152] Cochlear Implant International Community of Action (CIICA) : Sharing initial data from our survey of adults with CI: thanks to you all!. n.d.;

[153] World Health Organization (WHO) : Rehabilitation. 2021;

[154] FDA : Premarket Approval (PMA). 2023;